Traveling in Isan is always an adventure into the unknown, a surprise-filled journey through a version of Thailand not overly fussed with tourism. The Thailand of our grandparents’ generation where heat follows harvest, followed by rains, then the cycle repeats. And the delight of discovering something new at unexpected moments is a big part of Isan’s allure.

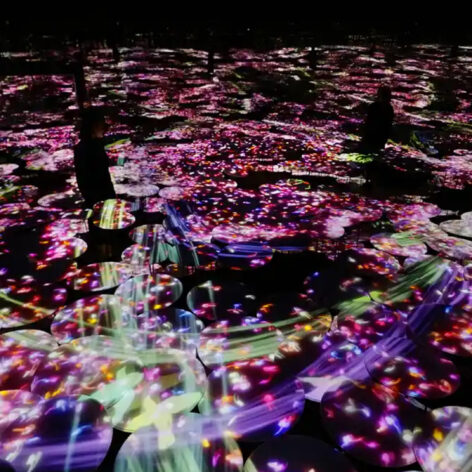

Guidebook in hand, I sit, close my eyes, and listen to the music of a traditional wooden loom. The flight of a shuttle — loaded with a bobbin of thread — skittering from side to side, accompanied by the rhythmic thumping of a beater, carefully tamping down each weft row of beautiful mutmee (ikat) silk. Thump, thump, thump. This pulsing beat can be heard anywhere in Asia, but here in Ubon Ratchathani, it carries even more significance. It’s the marching drumbeat of millennia of history.

Sitting in Ban Khampun, the elegant workshop of national artists Meechai Taesujariya and Khampun Srisai, I look around at the beautiful Lanna, Lao, Siamese, and Chinese styles fused into the low-slung buildings that encircle the long grassy courtyard. Their popular year-round textile museum and café occupy the plot next door, but Ban Khampun only opens to the public for three days each year. Here, I watch intricate traditional patterns reimagined onto heirloom-quality textiles which are highly sought-after and fetch high prices in Bangkok and beyond. The sound of the weavers’ pulsing toil allows me pause to meditate on this area and my journey thus far.

Take a look back at Ubon Ratchathani’s history

Ubon Ratchathani is a living pastiche; a crossroads of cultures. The province is nestled in the southeast corner of Thailand’s northeastern Isan region, flanked by Laos to the east and Cambodia to the south. An ancient civilization settled this area thousands of years ago, leaving behind impressive petroglyphs at Pha Taem National Park.

Fast forward to the late 1700s and an aristocratic quarrel with the King of Vientiane caused several Lao nobles to move their entourages to an area on the Mun River, which became Ubon Ratchathani. The 20th century saw skirmishes with the French, waves of migrants fleeing turmoil in Vietnam, as well as an American air force base that poured money and cement into the city. These influences harmonize, swirl and fuse together into an identity that is truly unique — a sum greater than its parts — like the intricate and unique fibers woven into stunning textiles.